Making better progression systems

How to engage players in the long run

If you are not a Game Design specialist or want a shorter read, an abriged version is available here.

About a year and a half back I made the jump from being a Game Designer to being a Scout and Analyst for an indie game publisher. Most of my time in this role was spent looking at games and talking with developers to help them improve their project and potentially offer them a publishing deal down the line. One of the subjects that developers seemed most eager to get feedback on and/or receive help with was progression systems.

I can think of a few reasons why that is the case, one of them being the broader game design culture, most curriculums, talks, youtube videos and books tend to focus on the “core” aspects of the experience, like a game’s main mechanic, balancing or its 3C. Another one could simply be that the industry standard for progression systems has been evolving rapidly during the past few years. This also explains the lack of resources available on the subject (as of writing there is no publicly available GDC talk on progression systems for example).

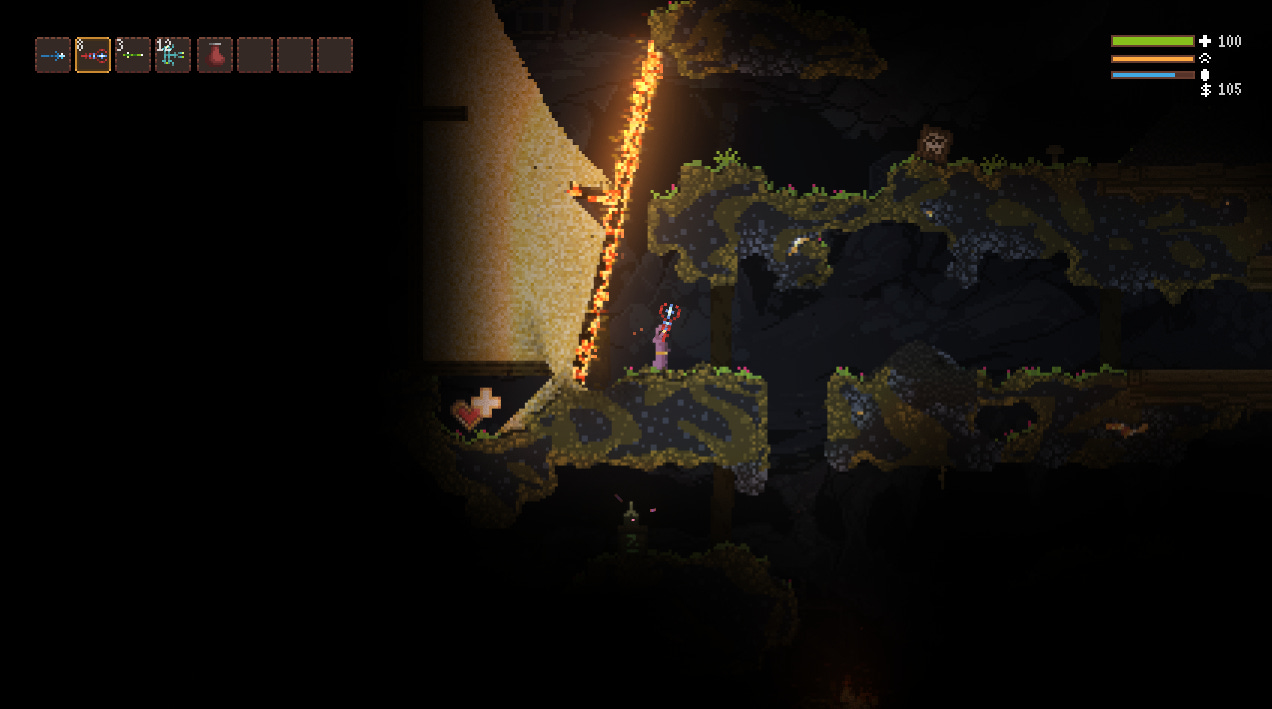

Shigeru Miyamoto had already figured out how to make a great platformer in Super Mario Bros. (1985), and a lot of the wisdom that was true back then is still found in Super Mario Bros. Wonder (2023). One of the biggest differentiating factors between these titles (putting aside artstyle and other differences related to hardware limitations) is their overarching structure and the way the player progresses between the levels. Likewise, while there was no progression system in Rogue (1980) and some content to unlock for future runs in The Binding of Isaac (2011), most roguelikes1 nowadays feature at least a basic progression system and sometimes a whole meta-layer of gameplay (see Moonlighter (2018) and Cult of the Lamb (2022)). Exceptions do exist of course but these tend to have another way of engaging the player in the long run. Noita (2019) for example accomplishes this through (1) having an in-depth spell crafting system that creates a sense of progression through discovering new spells and combinations, (2) a tough difficulty curve that effectively locks content away until the player is skilled enough to survive the earlier biomes and (3) an unparalleled physics system which enables tons of unique interaction.

In Noita, each pixel is physically simulated, including sand falling, destructible walls and floor, fire, etc…

These observations and the numerous conversations I’ve had with indie developers, publishers, friends, colleagues and bosses about this topic in the past few years prompted me to write this article.

Why should I care about my game’s progression system?

This is a reasonable question to ask. Each game aims to offer a different experience and many of them can do so without the need for a progression system. However, there is one reason that should make you seriously consider this aspect of your game, and that reason is that it gives the player a pretext to stick around.

You’ll see it if you look through your steam library, even successful games that offer a great core gameplay tend to have something on top of it that makes the player want to stick with the game. It may be a highly polished narration, it may be the sheer quality and quantity of content or it may be a good progression system. Great games tend to have more than one (Hades (2018) for example has all three). While all of them are very effective at making players want to come back, progression systems tend to be more attainable for small teams and indie developers than having highly polished content, visuals or narration.

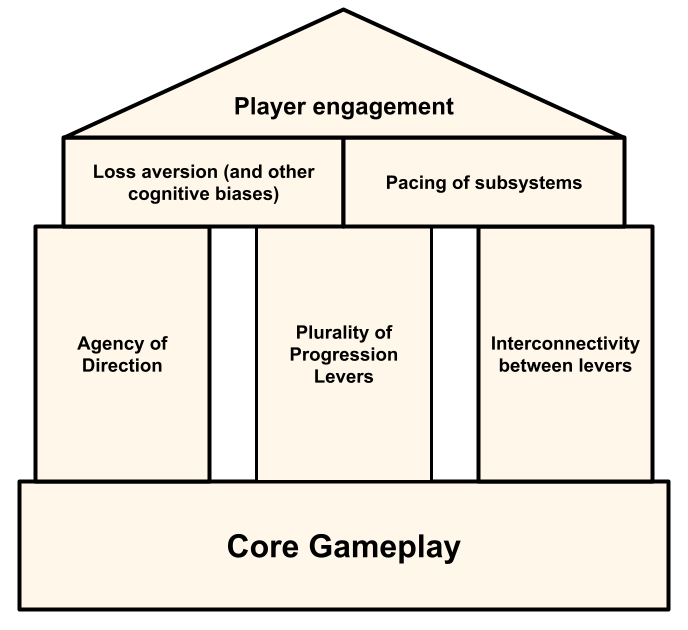

This is, in my opinion, what progression systems are truly about. They’re meant to provide anchor points to the player and give them a reason to experience the full extent of what the game has to offer. This article aims to highlight the different characteristics that allow a progression system to accomplish this goal. These are :

Agency of direction

Plurality of progression levers

Interconnectivity between levers

A healthy dose of loss aversion

Gradually introducing subsystems

The first three form the basis to create a system that’ll increase player retention without feeling like too much of a grind. The last two are a bit more advanced and are aimed at taking an already functional progression system to the next level.

Agency of direction

I first had the realization of how important this point is when replaying through Final Fantasy Tactics A2 (2007) (FFTA2 for short) a couple of years ago. To put it simply, in FFTA2 each character has four ability slots, two are for combat abilities, one is for counterattacks and one is for passive abilities. One combat ability slot is locked and will be always defined by your current job, however, the second combat ability slot (as well as the counterattack and passive abilities’) can be configured to use the ability set of any other jobs that this character has unlocked.

The first slot (yellow text) is set to my character’s current class and can’t be changed. The other three slots can be configured to any other skills they have learned.

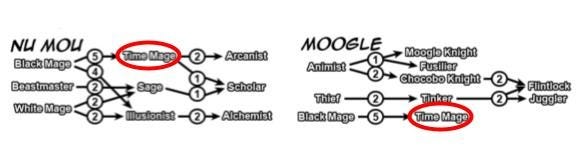

This opens up customization tremendously : do you want your Time Mage to be a full-on support? Pick the White Mage’s abilities as your secondary set. Do you want them to be a hybrid support/damage dealer? Use the Black Mage’s. Do you, in fact, really want a ranged physical attacker with some support abilities? Swap out your character’s job for a Fusilier and use the Time Mage’s abilities as your secondary set. The jobs your character has access to is restricted by their race, each one having access to a different job pool (see example below).

FFTA2 job trees for Nu Mous and Moogles (source : final fantasy wiki)

In the previous example, only Moogles will have access to both the Time Mage and Fusilier jobs, and only Nu Mous will have access to both the Time Mage and White Mage jobs. This means that jobs can also play very differently depending on the race of your character.

The restriction of having one of your two ability sets be the one of your active job also isn’t really that restrictive and in fact acts more like a guardrail to make sure your build remains at least coherent. If anything, this allows you to explore the system more freely as you know your character will always have one ability set that works well with their current equipment and stats distribution. Limiting either the potential for players to make a mistake in their build and ruin the experience for themselves or the impact of said mistakes is a key component in creating a system that encourages experimentation.

Another way to promote exploration of the system is to separate different aspects of your progression in a way that the player can experiment with one at a time and still have a viable build. This effect can be seen in Warframe, where most builds can be optimized to work at a reasonably high level, but truly optimized builds leave little room for originality. Thankfully, the game lets you customize your character and all three of your weapons separately, meaning that you have the room to experiment with one while keeping the others reliable. You can, for example, try out a new character (or character build) freely while still using your trusty over-optimized melee weapon that you know will destroy any high-level enemy in one fell swoop. This is another way to create player agency within your system: splitting up your build system in multiple independent parts and allowing each player to experiment within their own risk tolerance.

Warframe’s equipment screen, you can swap out your warframe (which is your character), your primary, your secondary and your melee weapon independently of each other. (source : Warframe subreddit)

These two games effectively create safety nets as they (1) guarantee a baseline power-level to the player whenever they step out of their comfort zone and (2) confine the risk to only a part of their build/their party when experimenting.

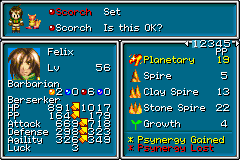

A good counterexample to this principle is the Golden Sun series. Leveling aside, the main way you progress is through capturing elemental spirits called Djinnis and equipping them to your party. While this system offers a lot of advantages, we’ll be looking at its main drawbacks here. Each game has a set number of 7 to 9 Djinnis per character evenly split between the game’s four elements. As characters are also split the same way you’ll typically equip the fire Djinnis to the fire character, the wind Djinnis to the wind character and so on. But the games also let you experiment with swapping them around which gives you access to different, more powerful classes : give your earth adept 3 wind Djinnis and 3 fire Djinnis and he’ll become a Ninja instead of his typical Lord class.

Change in abilities when swapping Djinnis (Source : Golden Sun Wiki)

However, as there is a fixed number of Djinnis, moving them around becomes a zero-sum game and soon the experiment you started on one character will have a rippling effect throughout your whole party. Instead of being able to try out a new class on one character you’ll have to change the class of your other party members as well which can make the whole experience overwhelming and uncomfortable for the player. Having small tweaks to your build create unexpected changes in other areas/characters will reduce the feeling of agency as you effectively are less in control of the risk you are taking. The player is then more likely to become mentally checked out and to stop engaging with the system altogether (which is the opposite of what we want).

Here are the things to keep in mind when designing a progression system that gives agency to the player :

Is there a reason to explore the possibilities offered by your system? How can you minimize the overlap between the experience that two players will have of your system?

Can the player shoot themselves in the foot when creating their build? What impact will a build mistake have on your experience? Can it be reversed?

Plurality of progression levers

Now even with all the freedom in the world, if your game only offers one mode of progression it can still end up feeling grindy and unengaging (remember when every AAA game started featuring a skill tree?). The title of this part is then pretty self-explanatory. The idea is to add variety in the ways you can engage with the system to keep the progression from feeling repetitive.

There are many great examples to illustrate this principle but I’ll only mention two here :

Cult of the Lamb’s approach of having the meta progression built up as a full on gameplay loop with its own systems/subsystems and the way it all ties back into your in-run combat abilities could be a case study in and of itself.

Cult of the Lamb - Cult Building gameplay

Even the Cult Building gameplay has its own progression subsystems

There is also some merit to splitting the roguelike portion of the experience into distinct biomes to make resource collection more of a deliberate task and promote player autonomy (Hades II has taken a similar approach with its two run paths).

Cult of the lamb lets you choose between 4 biomes whenever you start a run instead of having you go through them in succession.

Another good example to illustrate this is FFTA2. For one, it features an impressive number of subsystems (especially considering it is a Nintendo DS title), including an auction minigame, crafting, and the job system discussed above. It also makes a lot of smart design decisions that I haven't seen in other titles since. Chief among them is having the acquisition of new abilities tied to equipment. If your weapon has an ability for your job, you can use that ability as long as the weapon is equipped. After using it for long enough you’ll learn the ability for good and get to keep it even after unequipping your weapon.

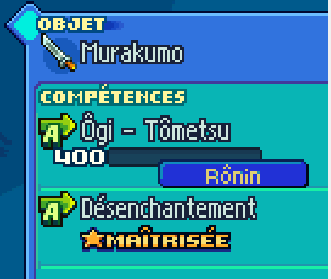

Here the second skill is mastered and will be usable when the weapon is unequipped, the first skill on the other hand will only be usable as long as the weapon is equipped until the character gains the required 400 points.

This has a lot of positive side-effects, from incentivizing looking for new equipment more often to foreshadowing powerful abilities for jobs you haven’t unlocked yet. Additionally, as you unlock jobs based on the number of abilities your character has mastered, this encourages you to build an extensive arsenal (using all means available, including the auctions) instead of having just the latest, most powerful gear on hand.

Interconnectivity between levers

Now if we just applied everything mentioned up until now we’d have a neat system that offers many progression levers to the player and also gives them the freedom to experiment. Some of these levers might have even grown deeper and developed into fully-fledged sub-systems. That’s great! There’s only one thing left to make this into a deep and engaging progression system and that is to ensure that everything connects back to the core aspects of the experience. As stated in the book Thinking in Systems2 : “Keeping sub-purposes and overall system purposes in harmony is an essential function of successful systems”. This point might sound the most obvious and yet can prove to be the trickiest to get right. One thing that I’ve seen consistently be a good indicator of how well tied together a progression system is is looking at the reward structure for a typical game session.

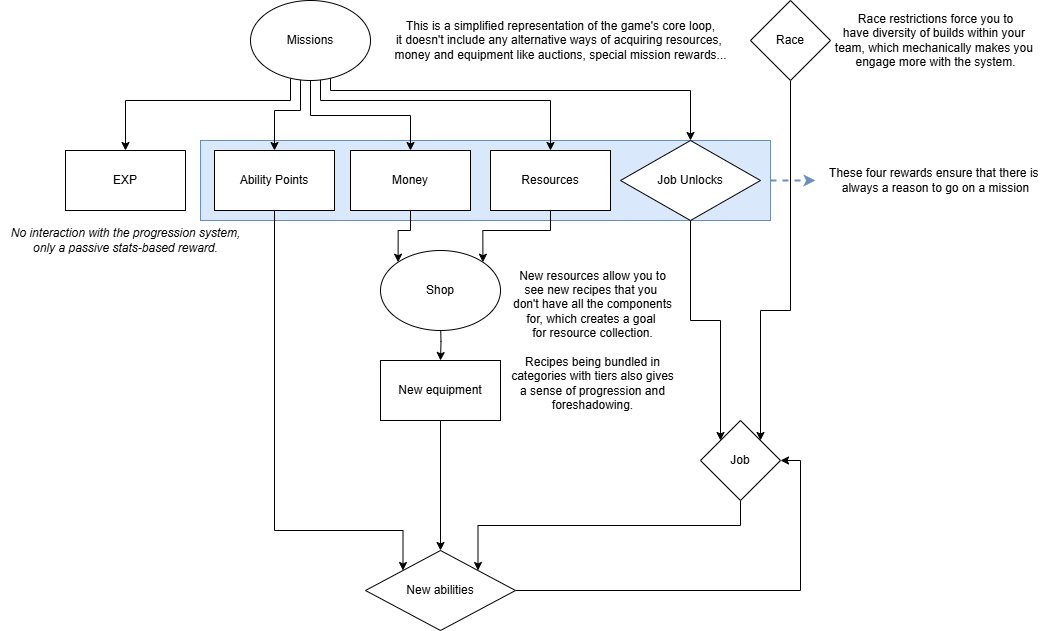

Looking once again at FFTA2 here we can notice a few interesting things. For now I’d like to focus on the high variety of rewards for a single mission.

Reward structure of Final Fantasy Tactics A2 : Grimoire of the Rift

For one, featuring several types of reward for the same part of gameplay like in FFTA2 ensures that the player will always be rewarded with something of use. This in turn helps keep their marginal utility (i.e. the benefit gained from each additional reward) high and avoids the feeling that they are becoming less and less relevant as the game progresses.

Notice also how every reward type offered for completing a mission ends up tying into developing a character’s set of abilities (the part that we saw was at the center of character customization in the first part of this article). To me this is brilliant design because what’s fun in FFTA2 is building up powerful characters and using their cool new flashy abilities in combat. Having every reward very closely tied to what you’d consider the “main fun part” of the game ensures that whatever the player does, there’ll be something new on that front. In other words, each action you take and each choice you make will come with unforeseen positive side-effects, making the experience ever so slightly better over time without degrading the feeling associated with rewards.

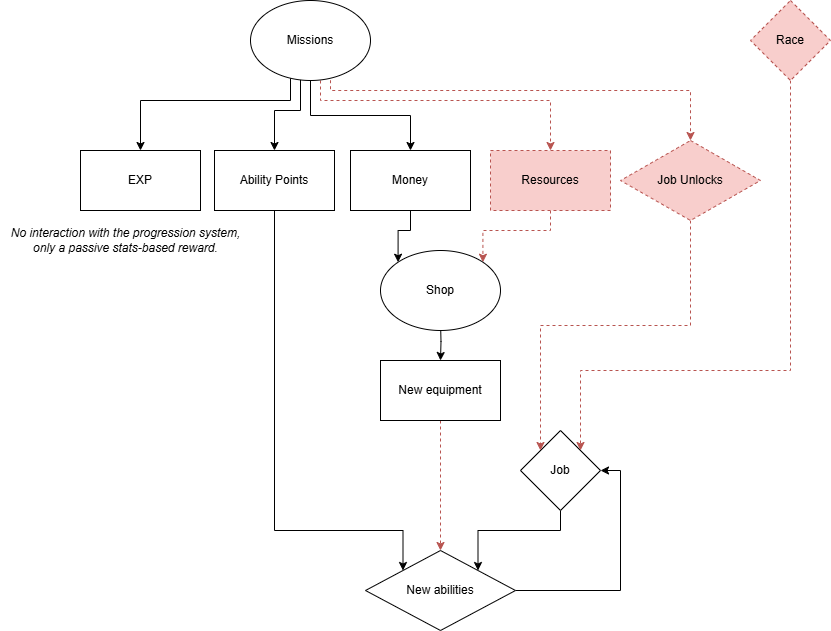

Looking at the same diagram for Fell Seal : Arbiter’s Mark (2018) (which is heavily inspired by the Final Fantasy Tactics Advance games) we notice that a few parts of the system are missing. I highlighted them in red for clarity.

Reward structure of Fell Seal : Arbiter’s Mark compared to FFTA2’s3

First off, all jobs (excluding DLCs) are unlocked from the get go and all non-story characters are humans. This means that nothing is preventing you from building every character in your party the exact same way. Overspecialization isn’t always a bad thing, but as designers I reckon we should be careful when giving the players the tools to achieve it, especially early in the game.

Another point is that equipment and abilities are completely separated. This is maybe the most significant difference as this means that the player can see the whole skill tree for each class right from the start, removing the excitement of discovering new spells. This also means that equipment is mostly just “money for stats” (since there’s no weapon crafting either) meaning you’re incentivized to sell all your equipment as soon as you can get something better because it won't be useful when spec’ing a new character. This makes trying out new jobs less appealing as you’ll rarely have any equipment on hand other than what your party members are carrying.

Despite a similar looking structure and almost identical core gameplays, both titles end up feeling very differently. Out of the 5 factors that influenced the learning of new abilities, three (crafting resources, race and job unlocks) are gone and one (money) is still here but no longer connects back to it. Abilities and jobs now form a closed loop which retains some of the same “flavor” from FFTA2’s system but removes most of the depth and excitement that could be found when spec’ing a new character. All of these changes make it tremendously harder to feel engaged in your character’s build.

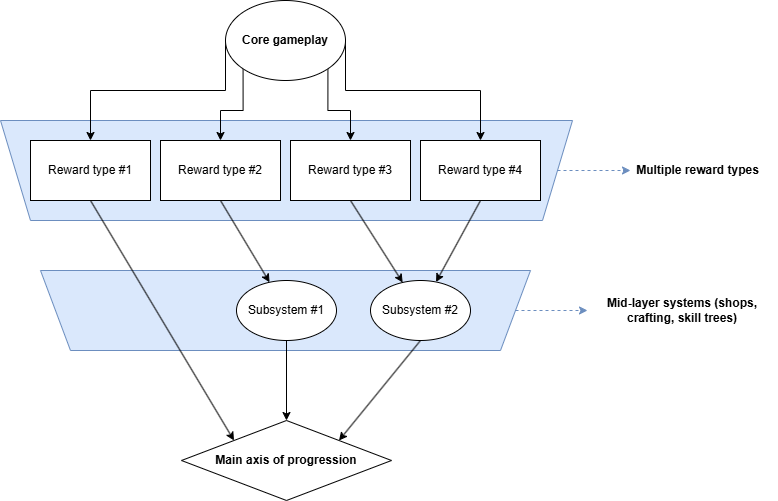

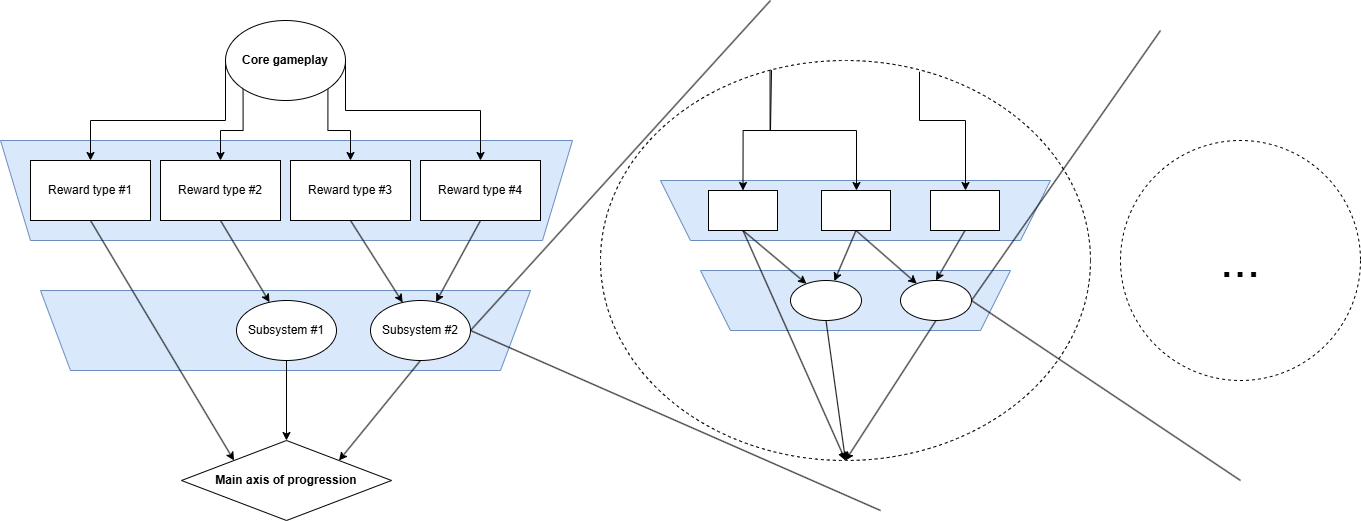

Looking at FFTA2’s diagram, we can actually generalize a lot of the design choices found there to build a more widely usable model of progression systems. I call it a “reward funnel” (see diagram below). The main goal is to have a somewhat complex system with a single source (every reward emerges from actions taken by the player in the core gameplay) and a focused output (the main way of gaining power within the game, which if possible should also be what is most exciting to the player).

Reward funnel - this model could also be represented as a loop with the very last step tying back into the core gameplay.

Each subsystem can of course contain its own loops and intermediate resources. On the opposite end some resources may be directly invested in the player’s main progression lever, with or without the need for interaction (as is often the case with experience points).

The subsystems can of course be as complex as required by the game and have their own offshoot subsystems.

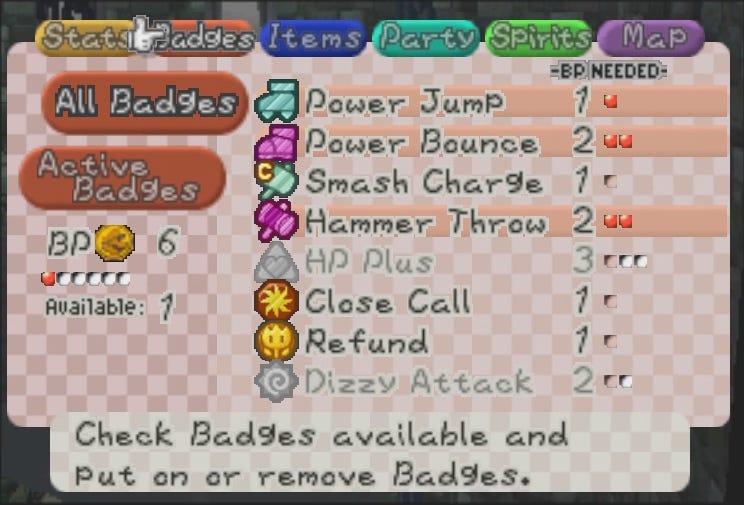

To see an example of this principle in a more linear/story-driven game, we can look at Steamworld Dig 2 (2017). Here the main progression levers (exploration, ability unlocks and story progression) all require mining, which also allows you to find different minerals to sell in town. The cash earned this way can then be used to upgrade every part of Dorothy’s kit, improving your resistance, damage output, water carrying capacity etc… which in turn unlocks unique perks (“Cogs”) with each level that act quite similarly to Paper Mario’s badges. This example is particularly interesting as the resource collection/upgrading loop (which is a positive side-effect of the core gameplay loop) has its own additional and separate positive side-effect.

Cog screen from Steamworld Dig 2.

Badge screen from Paper Mario (source : RPGRanked)

Now if you’re building a progression system from scratch or reworking the one you currently have, these three points should be more than enough to create a compelling experience (granted it is well implemented within the game). If, however, you’ve got a system that checks all three of these boxes and still want to take it to the next level then here are two more ways games keep their players engaged through their progression systems.

A healthy dose of loss aversion

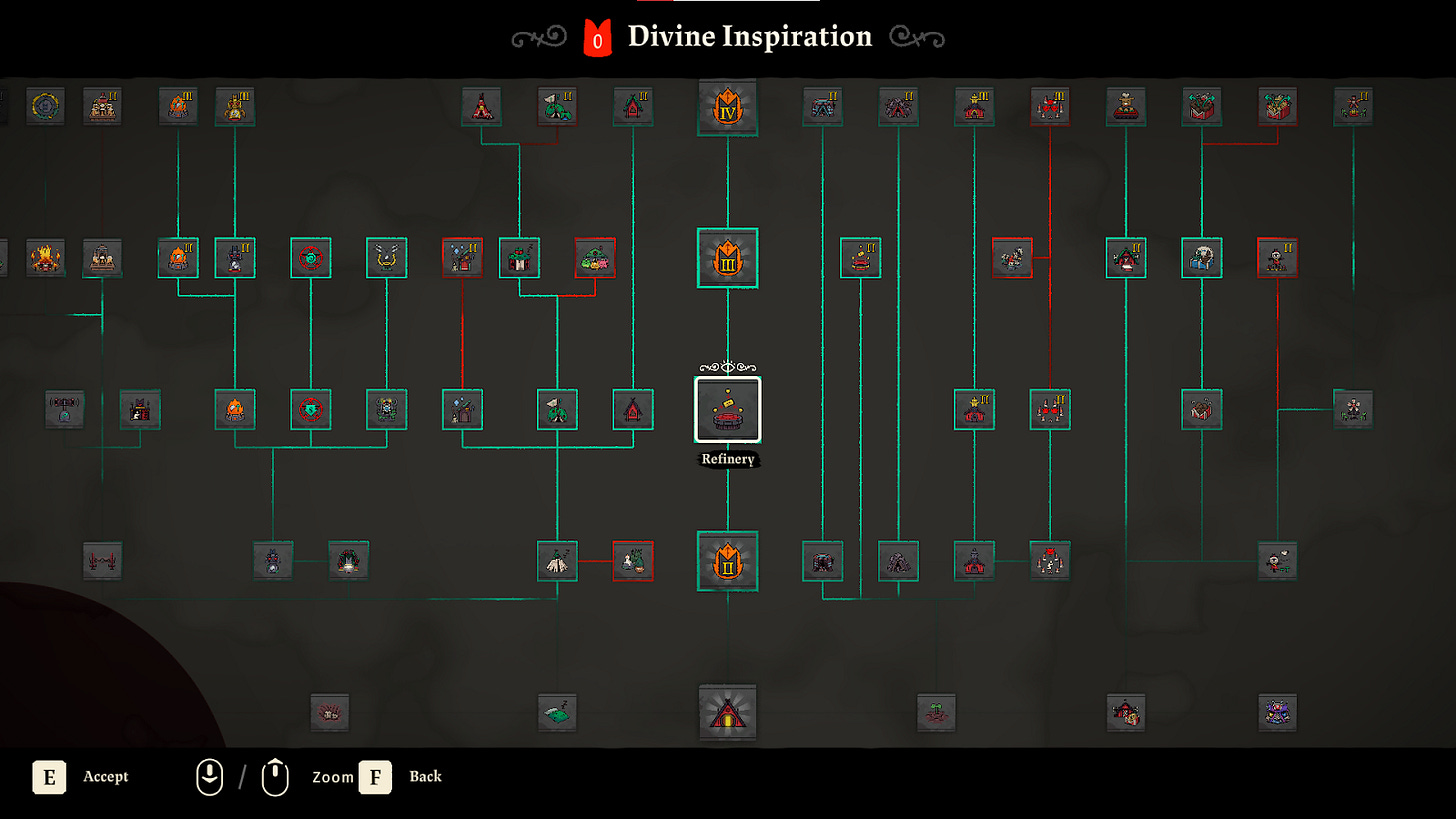

Now this one came as a realization when I tried out Final Fantasy XII : The Zodiac Age4 (2017) for the first time earlier this year and discovered its licence system. For a quick breakdown, in most RPGs you can either equip a weapon as soon as you find them or they are locked behind level/stat caps that you have to reach first. In FFXII:TZA however, weapons, armors and spells require a licence to be used by your character. These licences are acquired by spending licence points (a currency that’s obtained through killing enemies but is separate from gold and exp) in the licence board.

Licence board from Final Fantasy XII (source : Game Rant)

Unlocking a license allows you access to all adjacent licenses and thus you can navigate the board freely and build your character pretty much however you like. If you want to go around the section for mid-level swords because you found a high-level one already you can completely do that (and you might pick up some useful stat boosts along the way!).

Now why is this system particularly good at keeping the player engaged?

Picture this : you opened a chest in a dungeon and you found a cool new sword for one of your characters. Great! But there’s a catch, you need 40 more points to unlock the license you need to equip it. You don’t want to “waste” the weapon so you keep playing until you get the 40 missing points, unlock the license and finally equip it. But that’s not all, because now your five other party members also have an extra 40 points, which prompts you to go visit each of their boards and start thinking about their build. You might unlock the license for a new spell or equipment, and be tempted to visit the shop so as not to “waste” it. Before you know it you’ve got a newly upgraded party that you’re eager to go try out, and the cycle continues.

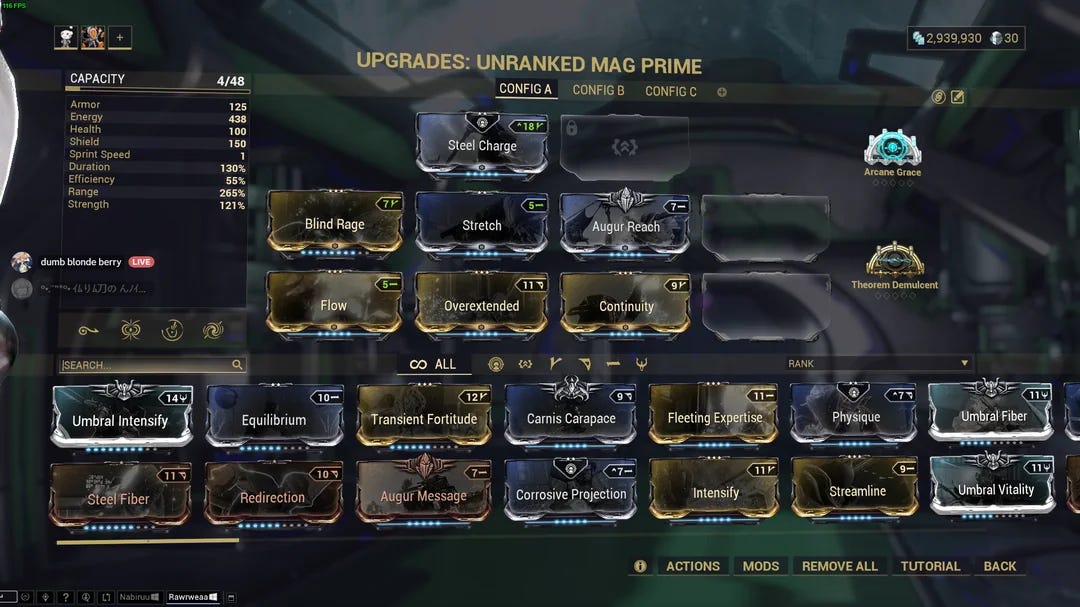

The key idea behind this system is separating owning something and being able to use it. Because we have a natural aversion to losing or “wasting” what we own, we want to keep on playing to make the most out of it. Warframe also uses a similar effect with its upgrade system (called “mods”). Even at max level, warframes and weapons don’t have the capacity to equip maxed out mods in all of their slots, so the player is incentivized to grind in order to put them in a state where they can fill all the mod slots (by formatting them and installing reactors) in order to avoid “wasted space”5.

Warframe’s mod screen (source : Warframe subreddit)

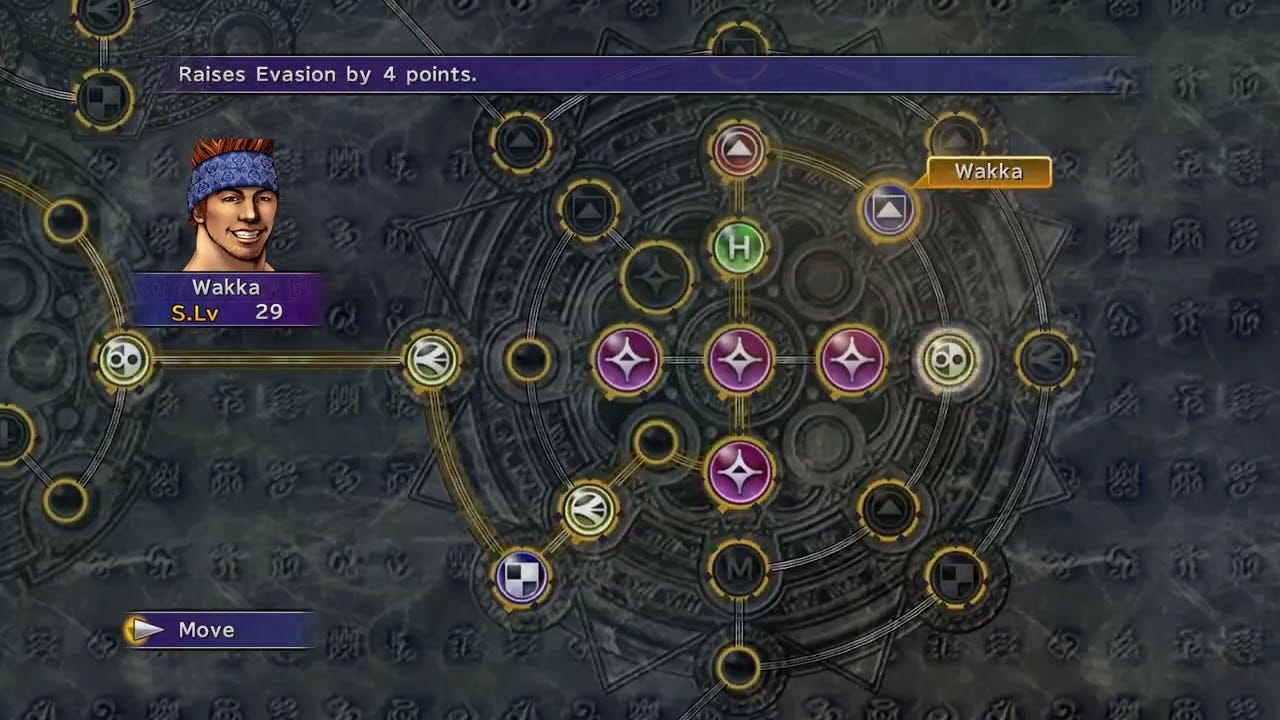

A good counterexample of this effect actually comes from the previous single player RPG in the Final Fantasy series. In Final Fantasy X (2001), the different characters progress along a talent tree called the “sphere grid” by placing spheres in predetermined positions. This kind of design typically means that the player can plan all the way to their target upgrade for each character. Reliability and predictability can of course be good in many scenarios, but here it comes at the cost of two things. For one, there is little to no variance in the way players will build their characters (echoing the “Agency of Direction” part of this article), you’re always treading one of the paths that were created by the designer. Secondly, there is no pressure on the player, whichever node you want to reach you’ll get there eventually. You don’t lose or waste anything by picking one option over another, you’re just choosing which one you want first.

Sphere Grid from Final Fantasy X (source : FFX Overpowered Guide)

Playing with both games side by side, we immediately notice that having to choose between a few impactful options at every step of the way is more engaging than navigating a bigger talent tree with mostly stat upgrades. Even though the abstract structure of both systems may be the same, making players work through half a dozen non-gameplay altering upgrades before getting a new ability means that inconsequential choices may tunnel the player towards a certain upgrade path as opposed to them making a conscious choice of “choosing upgrade x over upgrade y”.

As a side note, it’s also worth noting that the Sphere Grid is mostly the same for all party members, the only significant difference being their starting spot. This approach was originally the one that was taken in FFXII but they did away with it in the Zodiac Age version in favor of a hybrid system with twelve individual jobs corresponding to twelve separate boards. This is a pretty big improvement as it makes it easier for first time players to engage with the system by wrapping it in a recognizable surface layer that’ll make sure your build structure remains coherent (echoing once again a point made in the “Agency of direction” part of the article).

With the correct dosage, loss aversion can pose as a low-friction incentive and lead to very enjoyable experiences without the player ever noticing it’s there. Cognitive biases are typically exploited by free-to-play titles (especially in monetization features like lootboxes, battle passes and gacha mechanics) but there’s a lot of potential in using the current knowledge that we have about them in ways that make games more fun and memorable without preying upon the players’ wallets. Funnily enough, a great example of that can be found in Supercell’s fifth free-to-play title Brawl Stars (2017) where they decided, after removing paid lootboxes in favor of linear progression6, to add them back into the game as a non-purchasable free gameplay reward. These were received extremely positively and seem to have had a positive impact on both player count, player retention and game revenue despite being entirely cut off from the game’s monetization.

Starr Drops from Brawl Stars are a free reward that reuse a lot of the UX tricks developed for paid lootboxes. (source : GDC)

Gradually introducing subsystems

So you’ve got a well-integrated progression system that’s both engaging, rewarding and adds to the overall experience. Great! But how do you know it will stay that way for the entire playthrough?

Once your player has figured out the working of your system and built a mental model of it, the game becomes predictable and you’ll run into the same issue mentioned previously where your progression path is obvious, or “solved”. So how do you make sure your system stays fun once the player has figured it out? Well one solution is to expand the scope of your system, either by holding back or limiting certain parts in the beginning, or by introducing entirely new systems and content that will challenge the player’s understanding of the game. The goal is to add it right when the player feels like they’ve wrapped their head around the system they’ve been presented with and it becomes predictable to them (this can also be paired up with story beats for better effect!). We can find many example of this in both recent and older games, only looking at titles I’ve mentioned in the article we have :

FFXII:TZA adds a lot of depth to character building by introducing the ability to pick two classes for each character right about when the player starts having a good grasp on the system.

Cult of the Lamb adds a whole subsystem centered around sin once you’ve defeated three of the four main bosses.

Hades II introduces a new run type and lots of unlocks related to the resources found in the new biomes.

You can even look at the way live service titles and MMOs introduce new systems throughout the game’s life cycle. The experience of discovering a newly added system is, all things considered, very similar to the experience of unlocking a previously unknown subsystem or progression loop. I’ve already cited Warframe earlier in this article and it is a prime example of this principle.

Conclusion

It is undeniable that progression systems have proven to be excellent tools to increase audience retention and allow them to enjoy the game for longer. The design philosophy behind certain genres like roguelikes has completely been transformed and is barely recognizable from ten years ago.

Even if the recommendations presented in this article aren’t relevant to your particular project, I hope it got you thinking about engagement and how players will or will not develop a rapport to your game in the long run. There is more discourse about “hooking the player” than ever before in the games industry, and yet surprisingly little time is dedicated to asking how the player remains interested after a couple (or a couple dozen) hours. This also ties back to another trendy subject in the game dev space : building a community. While this is (rightfully) most often addressed through the lens of marketing and social media presence, it is also worth noting that players will be more likely to engage with a community if they want to stick with the game in the first place. It is then important that we as designers acknowledge their untapped potential and strive to make improvements on what is, all things considered, still an underexplored area of our field.

Some people elect to separate rogueliKes and rogueliTes based on whether or not the game has a progression system. I personally find the distinction to be rarely helpful both in terms of design (progression systems are more of a spectrum than a “true or false” thing) and in terms of marketing as players tend to buy either one indiscriminately.

Donella H. Meadows (2008).

There is one non-human character in the game which uses monster moves. As it is only a one-off character and no other non-human can be recruited, I didn't take it into account when drawing up a representation of the system.

This version features a slightly different version of the license system from the original with the board being broken down in 12 different classes instead of one megaboard and the player having the ability to respec at any point during the adventure.

Of course, the needed resources also need to be farmed separately (formas and reactors for the equipment, endo and credits for the mods), which are their own separate loops in and of themselves.